Amy Kazmin in New Delhi

© Financial Times, 28 October 2019

Reproduced with permission from FT syndication

New Delhi’s Gandhi Nagar market is one of India’s largest garment wholesale hubs, jammed with inexpensive, ready-made garments for the aspirational but price-sensitive lower middle class. The vast array of kids’ party wear, elaboratelyembellished jeans and other clothes draws traders from across north India, who stock up on merchandise to sell in small-town shops and rural bazaars.

Typically, the run-up to the annual Diwali festival is the market’s peak season, when the narrow lanes are so jammed with buyers hauling clothes it is difficult to move. But this year, traders complain, the festive shopping season has been gloomy, with sales falling precipitously as a deepening economic slowdown hurts ordinary Indians.

Hit by lay-offs, pay cuts and reduced earnings, anxious consumers are tightening their belts. “For common people, these are luxury items,” says Sahil Nangru, 26, whose small business makes children’s outfits, selling them wholesale for around Rs500 ($7) a set. “People do not have money in their hands these days. Businessmen do not have money to invest.”

Weak consumer demand is fuelling a vicious downward spiral. In recent weeks, Mr Nangru and his partner, Pradeep Chawla, have shut down two of their four small garment-making workshops, and laid off 25 workers. “For the last three or four months, we’ve had absolutely no work,” says Mr Chawla. “Now because of Diwali we’ve had some orders. But if we have no business, we have to let the workers go, it is natural.”

The gloom at the market reflects the malaise in India’s economy, now under the spotlight after the hoopla of prime minister Narendra Modi’s security-focused re-election campaign – and his triumphant victory just six months ago.

Not that long ago India was revelling in its status as the world’s fastestgrowing large economy. It seemed on the cusp of its aspiration of growth rates of 9 to 10 per cent – the pace economists say is necessary to create sufficient jobs for the estimated 12m Indians entering the workforce each year.

But since the second quarter of 2018 – when gross domestic product grew at a brisk 8 per cent year on year, India’s economy has steadily lost steam. GDP growth sank to just 5 per cent in the three months to June 2019, its slowest pace in six years. And as the economy skids, India’s millions of self-employed, vulnerable contract workers and farmers have all taken a hit.

“People’s businesses have collapsed,” says Nidhi Varma, who runs a small shop in a Delhi mall, and has watched as other shops shut down around her in recent months. “People don’t have enough profit to pay rent.”

Before the election, Mr Modi’s government had brushed aside warnings of economic fragility, dismissing them as too pessimistic and politically motivated. But with the deepening economic distress impossible to ignore, debate is mounting over precisely what ails the economy, the root cause of the slowdown, and how long it will last.

New Delhi insists the difficulties are a cyclical blip, brought on by tumultuous international conditions. But many economists believe the slowdown is of India’s own making – the result of policy mis-steps, sluggish market-oriented reforms and Mr Modi’s failure to resolve problems in the financial system left by over exuberant lending during the previous Congress administration.

“Blaming it all on the outside is too easy,” Raghuram Rajan, former Reserve Bank of India governor, said in a recent lecture, his first on the state of the Indian economy since leaving the job in 2016. “India is poor. It has a lot of potential for growth on its own, without relying on the outside. Why aren’t we growing at 7 or 8 per cent?”

Private investment has been muted for nearly a decade since the global financial crisis. New Delhi has little fiscal firepower left for stimulus, with an annual public deficit – including the centre, states, and state-owned entities – estimated at nearly 10 per cent of GDP. Now, private consumption is faltering, as the public mood darkens, and easy consumer credit dries up after last year’s shock collapse of Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services, a major finance company.

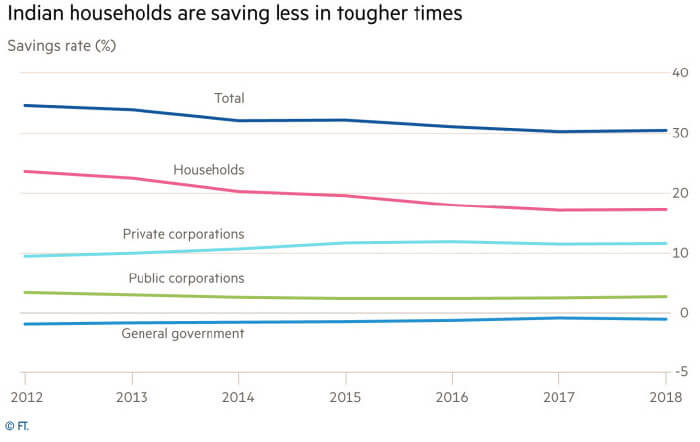

According to the most recent RBI consumer confidence survey, Indians’ optimism about their future prospects is ebbing away. Families have been living beyond their means, drawing down savings and taking loans, expecting better days ahead, government statistics show. From 2012 to 2018, household savings fell from 23.6 to 17.2 per cent of GDP. Household debt has risen sharply, though at 11 per cent of GDP it remains low by regional standards.

“There is a general environment of extreme risk aversion,” says Gagan Banga, vice-chairman of Indiabulls Housing Finance. “Today we have a situation where the business community in general is scared to invest, the consumer is scared to consume, and lenders are scared of lending both to business and consumers because they feel that the money will get stuck.”

India’s automotive industry – which accounts for around 40 per cent of manufacturing GDP – suffered a contraction in passenger and commercial vehicle sales of 23 per cent year on year from April to September. Sales of motorcycles and other two-wheelers – often a leading indicator of the strength of the rural economy – contracted 16 per cent. Other industries, from fast-moving consumer goods to aviation, are slowing.

India is forecast to grow 6 per cent this financial year, but some see that as over-optimistic. Arvind Subramanian, the government’s former chief economic adviser, dropped a bombshell in June, when he argued that India’s official GDP statistics probably overstated growth by 2.5 percentage points a year from 2011-12 to 2016-17.

Though the government has rejected his claim, many economists in India and abroad have questioned the credibility of India’s headline GDP growth in recent years, which have often appeared at odds with weaker underlying data. Mr Subramanian, who says he raised his concerns about the data when in government, believes India has been struggling since the global financial crisis.

“The malaise is not recent,” he said recently. “Essentially, India never recovered from the global financial crisis. Investment and exports – the main engines of growth for developing countries – have never recovered.”

Others believe Mr Modi’s policies – to clean up and formalise a notoriously corrupt business culture – have also taken a toll, inflicting severe disruption on two of the country’s most employment-intensive sectors.

His draconian 2016 cash ban – through which 86 per cent of the country’s currency in circulation was invalidated overnight – and the chaotic rollout of a new tax system were knockout blows for millions of small, informal enterprises that had operated beyond the tax net. Many could not cope with either the goods and services tax’s technical or financial demands. Real estate was also hard hit, leaving developers with a vast inventory of unsold and unfinished buildings.

“The sequence of demonetisation and the GST essentially was the straw that seems to have broken the Indian economy’s back,” Mr Rajan said.

The aggressive anti-corruption drive has also unnerved corporate India, deterring investment. Businessmen say officials seem to view all entrepreneurs as inherently suspect, and treat corporate distress as evidence of deliberate malfeasance.

“Many parts of business in India were like a dirty white shirt,” says Uday Kotak, chief executive of Kotak Mahindra Bank. “India needed to clean it with soap and a wash, but we must take care that in the wash process, we avoid tearing the shirt.”

But it has left many businesses struggling to deleverage and survive the crunch. “There was an underlying shakiness and shoddiness in lending and governance standards,” says Saurabh Mukherjea, founder of Marcellus Investment Managers. “The general prosperity in the country and the abundance of black money masked that shoddiness. As the tide of black money goes out, you can now see who is standing naked.”

It is a far cry from the kind of job-generating economic boom Mr Modi was expected to deliver back in 2014, when he promised to bring “good days” to a young, restless population. “It’s a crisis,” economist Abhijit Banerjee said days before he won the Nobel Prize this month. “People are poorer now than they were in 2014-15.”

In public, Mr Modi, and his cabinet, still talk grandly of India – now a $2.9tn economy – growing into a $5tn economy by 2024. Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has blamed the auto industry’s woes on millennials, who prefer using Uber to car ownership. A government minister pointed to the strong box office take for the latest Bollywood films on their opening weekend as evidence of India’s sound economic fundamentals. Members of Mr Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party insist that the recovery’s “green shoots” are visible.

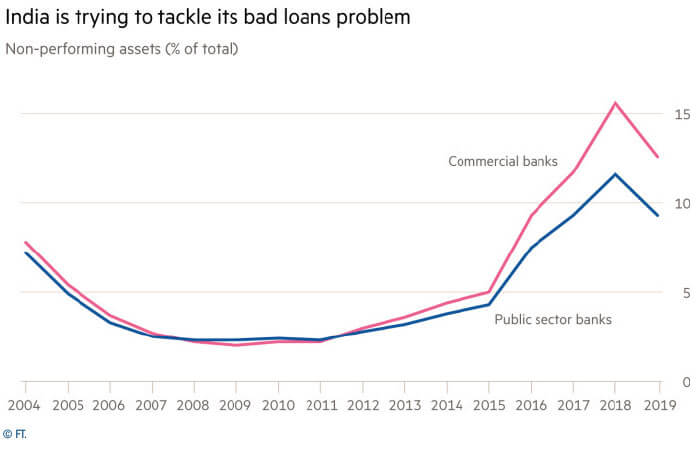

Independent economists warn that India’s many serious vulnerabilities – including overstretched public finances and the fragile financial system, including shaky shadow banks – will continue to weigh on the country’s prospects.

They say New Delhi has failed to recognise the severity of the financial system’s non-performing loan problem, or the risks posed by the fragility of shadow banks and housing finance companies, which are themselves big borrowers from mainstream lenders. Rating agency S&P has also warned of the rising risk of contagion from the possible collapse of shadow banks.

“The financial system is jammed and firms are reluctant to invest – and this is at the heart of India’s challenge,” Mr Subramanian said, calling New Delhi’s “underrecognition of how serious the problem is” a major hurdle.

New Delhi boasts of stopping politically-directed lending to influential tycoons, once a pillar of the state banks’ business model. But as it struggles to revive growth, it is pushing lenders to ramp up credit to small enterprises and households instead. During a recent nine-day “loan festival”, lenders pushed out $11.5bn in credit to small borrowers, raising questions about due diligence.

“A public sector dominated banking system cannot serve the needs of an expanding economy,” says Ila Patnaik, professor at the National Institute for Public Finance and Policy in New Delhi.

Mr Modi’s unassailable political position gives the government a freer hand to push through contentious, market-oriented economic reforms. New Delhi just announced a $20bn corporate tax cut to make India a more competitive investment destination.

Amitabh Kant, chief executive of Niti Aayog, a government thinktank, says privatisation of state enterprises, and major reforms in sectors like agriculture and mining, are on the agenda. He also insists recent painful disruptions will bear fruit with the emergence of a healthier business sector. “This government is fully committed to a high trajectory growth path,” Mr Kant says.

Mr Kotak is also cautiously optimistic that India will gradually bounce back, especially if fresh steps are taken to tackle the shadow banks. “We will take some time to navigate our way out of this – it’s not something that will happen overnight,” he says. “But in India, it’s never as bad as it looks. And it’s never as good as it looks either.”