Central banks around the globe have cut shortterm policy rates to at or below zero, re-introduced bond purchase programmes to lower interest rates along the duration curve and provided abundant liquidity to banks to increase credit availability to companies and households.

Despite this sizeable response, it is clear the pandemic will still have a major negative impact on global economic growth. The IMF predicts global GDP will fall to -3% in 2020, the worst since the Great Depression and significantly worse than the -0.1% recorded in 2009 in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC).

Adjusting to the “new normal”

But what about credit and debt markets? Here the narrative is quite different. First, we need to look at the backstory.

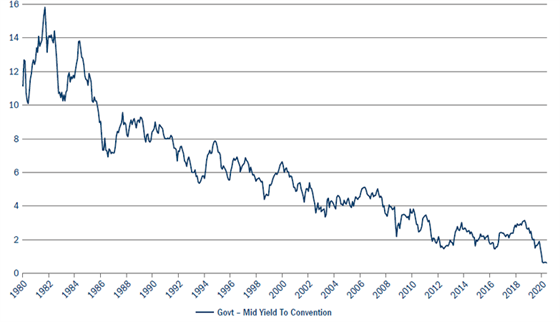

Over the last 40 or so years, nominal and real interest rates (after taking into account inflation) have been declining across the developed world. In the US, the Fed Funds rate, the interest rate at which banks and credit unions lend money overnight to other depositary institutions, has fallen from over 20% in 1981 to just above zero. Over the same period, yields on 10-year US treasuries have fallen from peaks of almost 15% to current levels of around 0.6% (see Figure 1). A similar picture emerges globally, particularly in the UK, Europe and Japan.

Figure 1: interest rates have been declining steadily for 40 years

Fed funds rate, 10-year us treasury yield (since 1980)

Source: Bloomberg, June 2020. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

This long-term trend is set to continue. The widespread view among investors is that interest rates are set by the central banks. We believe this is wrong. Instead, central banks are chasing a “natural” interest rate for the economy. This “natural” rate has been declining for many years and for a number of structural reasons, from ageing populations to stalling productivity growth (both of which are acting as drags on economic growth).

Indeed, were it not for the GFC, we believe we would already have negative interest rates in more western economies, including in the US. A massive increase in global debt issuance during the GFC dramatically increased the supply of benchmark bonds, helping keep bond yields artificially high.

Old policy levers less effective

The reality is that central banks have been discovering in recent years that traditional policy levers such as interest rate cuts are proving less effective – as shown in regions such as Europe and Japan where negative interest rates have still not proven sufficient to spur renewed growth. It’s not that central banks are losing their influence. It’s just that they are having to fight much harder to achieve the same result, turning to a wider array of extraordinary measures in large part because they cannot cut interest rates much further.

There are already early signs of how markets will respond. At the time of writing, yields on five-year Japanese government bonds and five and 10-year German bunds are negative. Yet, despite this, these benchmark government bonds remain great absorbers of shock: investors are still attracted by the security and liquidity of these investments.

Further, as interest rates have declined, capital returns for bond investors have increased. Over the last five years, during periods of equity market sell-offs, the pace at which interest rates declined was much higher than in the previous five years, giving bond investors healthy capital gains. We expect this trend to continue as interest rates turn negative. Indeed, the capital gains that bond investors get over the next five years could be even better than the last five.

Three key barriers to negative rates

So, what could change this story? We see three possible risk factors that could stall the shift to negative interest rates.

Even if it seems unlikely, we cannot rule out a productivity renaissance over the next five to 10 years (a move which would require serious public and private sector investment). This would spur healthy wage growth and with it interest rate rises. Clearly such an outcome would be positive for risk assets such as equities and negative for bond investors. But it remains a low likelihood in our view.

The second risk factor is government spending. Amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, governments worldwide have turned on the spending taps, ramping up their fiscal deficits. We expect much of this government spending to be temporary, in which case, as we emerge from this crisis, our base case scenario remains a protracted recovery with very low growth and inflation and, in turn, much lower – and therefore negative – interest rates.

But we cannot rule out some elements of fiscal policy becoming permanent in Europe, China or the US (particularly with a US election on the horizon). Increased spending, if correctly targeted, could enhance growth and reverse any move towards negative interest rates.

The third risk factor is inflation. Over the last quarter-century, investors have enjoyed the benefits of a low inflation environment, increasing their real returns. The causes are wide-ranging but include an ageing population, technological changes and globalisation.

An increase in inflation, perhaps spurred by raised government spending, would clearly be bad news for both bond and equity investors if unaccompanied by a revival of economic growth. But, as we are likely to emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic with significantly higher debt, increased unemployment and reduced growth, a spike in inflation looks a relatively low risk in the near to medium term.

These are three main risks to our negative rates scenario. But they remain low in our view.

A slow recovery

By resorting to unconventional policy responses, many investors believe that the US Federal Reserve and other central banks have overstepped their mandates and, in turn, undermined normal market mechanics. We believe this narrative is wrong; ignoring the fact that western economies have become captive to long-term structural drags on growth like falling productivity and an ageing global population, headwinds that have been exacerbated by the current downturn.

Interest rates are, therefore, poised to turn negative in the US and some western economies and go deeper into negative territory in others in coming months. Investors take note: the great bond bull market rally has much further to run.